Education

An Overview of the Goat Meat Market 2012

tatiana Stanton, July 2012

(Cornell Small Ruminant Extension Specialist)

Originally presented in 2003, but updated in 2006 and again in 2012

Introduction

The survivability of our US meat goat industry is dependent on improving its accessibility and desirability to the huge base of goat meat enthusiasts right here in the US. Goat meat consumption in the US grew sharply during the nineties and has continued to increase gradually since then. The slaughter numbers at USDA inspected facilities increased more than threefold from 208,000 goats in 1991 to 647,000 goats in 2003, but have remained fairly level since then peaking at 659,000 (865,800 including custom and state plants) in 2008 and dropping to 612,100 (779,000) in 2010. In contrast, imports of goat meat into the United States have continued to increase substantially from 1749 metric tons in 1991 to 8462 metric tons in 2003 and almost doubling to 15752 metric tons in 2011. A metric ton is approximately 2205 pounds. If we assume a 33 lb. carcass (the average carcass weight quoted by most wholesalers), 15752 metric tons equals approximately 1,052,322 more goats.

Who is our customer?

Increased consumption is driven by 1) the popularity of goat meat with the diverse ethnic groups that immigrate yearly to the U.S. and 2) burgeoning culinary interest in authentic ethnic foods and lean red meats. According to the 2010 U.S. Census, approximately 13% of the U.S. population is foreign born with about 53% of first generation immigrants coming from Latin America and much of the remainder identifying themselves as Muslim. In the past, most immigrants settled initially in metropolitan areas making it relatively easy to concentrate marketing in these areas. Today, even though increased numbers of newly arrived immigrants are opting to settle in locations beyond the traditional gateway states, much of the goat meat demand is still centered in major cities. For example, only about 6% of the total U.S. goat population was raised in the Northeast US in 2010, but the same region accounted for 55% of the goats slaughtered in USDA inspected slaughterhouses. The low income base of many newly immigrated families, particularly refuges, may suggest that they will be attracted to cull animals and to frozen, imported goat meat. However, as families become established in the U.S., they hopefully become more upwardly mobile and financially secure. Even people on tight budgets opt to spurge on fresh, local goat for weddings, funerals, and holidays.

Australia supplies 97% of the imported goat meat sold commercially in the US. Most of the goat meat imported from Australia is harvested from extensively managed ''feral" (semi-wild) goats and slaughtered at modern, centralized in-country slaughterhouses specializing in lamb exportation. Carcasses or "six packs" (boxed as 6 primal cuts) are frozen and transported by ship to the U.S. The quality is inconsistent and profit is highly dependent on the exchange rate between U.S. and the Australian currency, decreasing when the U.S. dollar weakens. Theoretically, the increased strength of the Australian dollar observed throughout the last decade is less advantageous to Australia exports and should help sustain our domestic production. A benefit of imported, low value, year-round product is that it keeps families in the habit of consuming goat meat. However, a growing portion of Australian and NZ goat meat is available as flown-in Cryovaxed fresh carcass and retail cuts from export slaughterhouses approved by the USDA. United States goat farmers need to increase their market expertise, infrastructure, bottom line and product availability to compete with fresh imported product.

Much of the focus of the US goat meat industry should be on making it easier for consumers and processors to obtain the goat meat product they desire year round. We need to insure that the children of immigrants are encouraged to continue these dietary preferences. There is also a strong trend in the US for the consumption of farm fresh product. Promotion of US grown goat meat will be counterproductive if goat meat is available only sporadically, specific carcass preferences are ignored, people are made to feel unwelcome when seeking out goat meat through established channels, or if our marketing infrastructure collapses in on itself and offers all of us fewer marketing choices. We do not need to limit ourselves to seeking out only an "ethnic" market but we better make sure that we nourish and acknowledge this market as the base of our existing demand.

Processing and Management Requirements of some cultures

A first step in knowing the goat meat market is to understand the strict meat handling requirements of some cultures. Muslim consumers require their meats to be "Halal" or "lawful" to their religious scriptures. For many this means it should be slaughtered using "zabiha" methods. Halal requires that the animal must be humanely killed by an adult Muslim. However, some Muslims will accept Kosher killed meats (especially if halal is unavailable) and some will accept meat killed by a Christian processor.

During a zabiha kill, the animal faces Mecca and the Takbir (a blessing invoking the name of Allah) is pronounced while the animal is killed without stunning by holding its head back and using a quick, single continuous cut across the throat just below the jawbone to sever the windpipe, esophagus, arteries and veins forward of the neck bone. Ideally, the knife blade should be extremely sharp and twice as long as the width of the animal's neck. A hand guard is permitted for safety. Muslims also view any goat that has consumed any pork (including lard or blood meal) products to be unclean. Other feeds that might be categorized as ''filth" may also lead to rejection of the animal. A 40-day period prior to slaughter of "clean" feed will generally suffice.

During a zabiha kill, the animal faces Mecca and the Takbir (a blessing invoking the name of Allah) is pronounced while the animal is killed without stunning by holding its head back and using a quick, single continuous cut across the throat just below the jawbone to sever the windpipe, esophagus, arteries and veins forward of the neck bone. Ideally, the knife blade should be extremely sharp and twice as long as the width of the animal's neck. A hand guard is permitted for safety. Muslims also view any goat that has consumed any pork (including lard or blood meal) products to be unclean. Other feeds that might be categorized as ''filth" may also lead to rejection of the animal. A 40-day period prior to slaughter of "clean" feed will generally suffice.

Kosher kill requires that the animal be killed without stunning by a specially trained religious Orthodox Jew, called a "shochet", using a properly sharpened special knife with no hand guard. The shochet also inspects the carcass and organs for defects. If the meat is to be certified as "glatt" Kosher, a stricter Kosher standard, the carcass from a small animal such as a goat must have no lung adhesions. The sciatic nerve and various veins, fats and blood are prohibited for Kosher consumption and must be removed. In most cases, rather than going through the difficult procedure of removing the sciatic nerve in the hindquarter, only the forequarter is marketed as Kosher and the hindquarter is sold through other marketing channels.

Federally inspected slaughterhouses need to apply for a "religious exemption"from stunning to conduct Halal and Kosher slaughter. The animal should either be killed on the ground (allowable only for non-inspected slaughter), straddled, or walked onto a double rail for a religious kill because it is inhumane to hoist and shackle the animal by its hind legs while still alive. Although there are national certification programs for Kosher and Halal processed foods, there is no national mandatory labeling and certification for Halal or Kosher meats. For the most part, it is your responsibility to insure that your meat meets your customers' definitions of Halal or Kosher.

Federally inspected slaughterhouses need to apply for a "religious exemption"from stunning to conduct Halal and Kosher slaughter. The animal should either be killed on the ground (allowable only for non-inspected slaughter), straddled, or walked onto a double rail for a religious kill because it is inhumane to hoist and shackle the animal by its hind legs while still alive. Although there are national certification programs for Kosher and Halal processed foods, there is no national mandatory labeling and certification for Halal or Kosher meats. For the most part, it is your responsibility to insure that your meat meets your customers' definitions of Halal or Kosher.

Certain African, Caribbean, and Oriental cultures prefer carcasses to be scalded or singed as part of the processing. A federally inspected slaughterhouse needs to include this step and describe how they will maintain food safety in this process in the mandatory hazard analysis portion of their HACCP (Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point) Plan.

Improving our accessibility

How do we make product available year round? Over the years, we have probably been lucky to have a supply of Australian goat meat for consumers to fall back on when US meat is scarce. However, this encourages distributors to abandon the US industry completely and market exclusively imported product. If we plan on expanding our US goat herd (and as we all know, goats multiply quite easily), we need to develop a base of producers who are willing to manage their herds more intensively either through accelerated breeding cycles or staggered kiddings to provide product more reliably year round. This is hard to do. Most of us are inclined to target peak demand times with their accompanying higher (sometimes) prices. Additionally drought conditions for many years in some of the traditional goat rearing regions of the US have made herd expansion unreasonable for many farmers.

How do we make product easy to find? We need to be assertive about finding new ways to contact different cultures about local availability of goat meat. Visiting mosques and foreign student associations, handing out business cards at auctions, sending press releases about their farms to cultural news journals and establishing on-farm live animal markets are some actions producers have taken. Promoting goat meat at local food venues and activities is an important way to make sure that it is included in the local food movement. These events provide an excellent opportunity to introduce consumers who have never had the opportunity to eat goat meat before to the product.

How do we provide sufficient supply even for special holidays? As producers, more of us need to group together to pool animals for sale. These groupings do not need to be formal cooperatives particularly if they are 1) targeting one particular distributor and 2) the products are live slaughter goats. In order to easily locate dealers, distributors, packers, processors and transportation, we need to encourage the accumulation of web based marketing services directories across more regions than just the Northeast US. The number of smaller USDA slaughterhouses willing to slaughter sheep and goats are decreasing at an alarming rate. Whenever possible, goat ranchers need to educate themselves about the effect of specific food safety regulations and government policies (federal, state and local) on these small and very small processsors who form the core of our goat meat processing facilities. Having easy places for producers to find contact information for buyers also increases our accessibility. However, many producers do not have the time to seek out buyers and investigate their credit status. Many buyers are also hesitant to deal direct. The formation of producer associations and development of large, graded sales where goat kids are grouped according to weight, age, and condition for a multitude of buyers can help link farmers to buyers. As part of this we need more sales willing to sell goats by the pound and more sales where prices paid are put on public record by a disinterested third party.

Improving our desirability

Bob Herr, a popular order buyer at the New Holland Sale, likes to say that there is a customer for every goat, a goat for every customer. It is important that producers educate themselves about the types of goats that are popular for various seasons. It is also important for producers to communicate well with their buyers to make sure they are accurately representing their animals and matching the animal to the market demand. This does not mean that the market is stagnant or does not appreciate some education from producers themselves. Many of us who have been in the meat goat business for a while can remember when customers were initially leery of meatier, possibly fatter, Boer X carcasses. Many immigrant customers desire a tender, younger meat once both the husband and wife are working and faster cooking dinners become a priority. However, knowing how to contact and communicate with buyers and getting educated about the market is a first step in meeting customer desires.

Many ethnic customers are proud of their ability to judge the carcass suitability of a live animal. New York City has a long history of live poultry markets and in recent years many of these have expanded to include small ruminants. An animal can be purchased at them and then slaughtered at the on-site custom slaughterhouse. This is one market that Australia cannot compete with us for. However, not all state departments of agriculture may not be aware of the importance of these markets and could potentially subject them to excessive regulation. Organizing annual meetings between state agriculture officials and representatives from statewide lamb and goat producer associations may help these agencies stay in touch with industry priorities. Live animal markets generally provide a wide range of animals to satisfy the diverse market demands of various cultures. In states where they are permitted, they provide a way for city dwellers to insure their own quality standards.

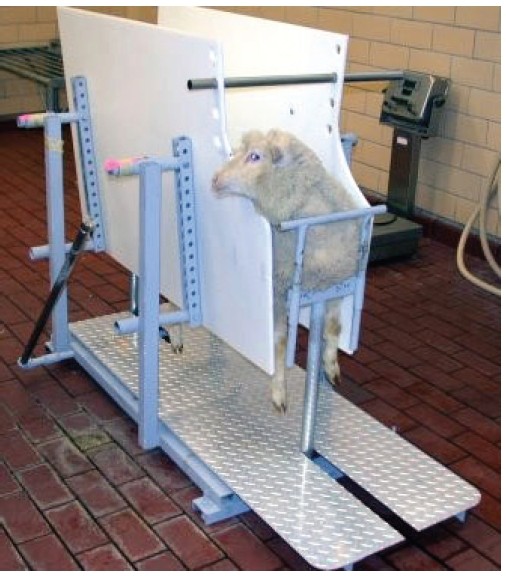

Desirability and acceptability of goat meat products for the general US public will be improved if slaughterhouses with religious exemptions handle animals as humanely as possible. As producers, we need to exert pressure on slaughterhouses conducting religious kills to adopt proper equipment.

Marketing strategies to get a bigger piece of the pie

There are many marketing strategies that producers can adopt to reap more of the market share of their goats. Almost all of these require an investment in extra labor and/or capital on the part of the producer.

One of the easiest marketing strategies is pooling. This is the gathering of animals from several farms together at one centralized pick-up point to offer a buyer a sufficient supply of animals. However, there are pitfalls that must be addressed in market pooling Often arrangements need to be made for one person to represent all of you in negotiating price and to assign or pay a person to insure that animals meet the quality standards of the buyer. In the fall '2002, the Northeast Sheep & Goat Marketing Program at Cornell University helped link a pool of producers up with a live animal market in NYC. This live animal market had its own livestock truck and was thus able to deal directly with producers. Farmers were paid $1.15/lb live weight for weaned kids weighing 55 to 100 lbs minus an estimated 4% shrink. The buyer also paid $.85/lb live weight for cull does minus 4% shrink. The arrangement was sustained through the winter and early spring but eventually folded. Problems arose because 1) producers were unable to provide sufficient quantity of consistent product year round, 2) shrinkage loss was very variable from one type of animal to another (for example, fat cull does versus recently weaned kids), 3) the buyer could not find a reliable driver and thus trucked himself and had to justify his time away from his business, 4) the marketing coordinator found it difficult to enforce quality standards if the buyer did not proactively speak out on questionable animals.

Another way to deal directly with buyers is to organize on-farm live animal markets. These work when farms are within commuting distance to metropolitan areas with large meat goat consuming populations. They are dependent on your state having a relaxed interpretation of the exemption for custom slaughtering of farmer owned livestock. Similar to the NYC live animal markets, customers come on farm, purchase an animal and have it slaughtered at the on-farm slaughterhouse. These live animal markets often need to purchase animals from other farms to meet their demand. For example, a goat producer located between Buffalo and Rochester, NY found that despite raising approximately 150 kids from his own farm, he needed to purchase 490 goats from 17 other producers in 2003 for an average price of $70.72 to meet the needs of his live market/custom slaughterhouse business. He also purchased 162 goats from local auctions averaging $55.32 per goat.

Cuisine from goat consuming cultures has grown in popularity with an increasingly cosmopolitan U.S. mainstream population. The healthy profile of goat meat is also attractive to today's consumer. The goat cheese industry has done a lot to destroy the public's inhibitions against goat products and many people who pride themselves on a discerning palate are interested in trying goat meat. Producers can opt to market retail cuts direct to restaurants and consumers. A disadvantage of selling particular cuts to restaurants is the need to find a use for the rest of the carcass. Many ethnic restaurants, however, prepare recipes that use the whole carcass.

Selling direct to businesses is very labor consuming. It is best done either by producers who raise a diverse range of products and thus save time by marketing a multitude of products to each of their customers, by large producers raising goats fulltime, or by formal cooperatives. Another option is for a group of producers to get together and market directing to a buyer for one or two particular holidays each year when demand is high and may absorb their entire kid crop. Even when done by a cooperative, it is recommended that products be identified by farm name regardless of the overall brand. Many of the restaurants and retail stores interested in buying direct from farmers want to emphasize the actual farm source. A farmer or cooperative that breaks into the retail market or markets a branded product to distributors needs to insure that the price received will compensate them for the extra time needed to coordinate slaughter, processing, transportation and regular communication with buyers.

Tables 1 through 3 show actual prices received and expenses incurred for suckling Boer cross kids in 2004 through 3 different Northeast marketing channels. Table 1 represents an informal grouping of goat producers for Easter where one producer acts as coordinator and absorbs some of the costs himself. For example, the coordinator paid for all telephone calls associated with the shipments, purchased the plastic shrouds for wrapping carcasses, and steam cleaned and lined in plastic the stock trailer and pick-up trucks used to transport the carcasses. Dressing percentages ranged from 63% to 57 % although a few animals dressed as low as 50%. Cooler shrink from slaughterhouse to retail store ranged from 6.4% to 2.6%. Average carcass weight was 21 lbs. Farmers received returns of about $1.73 to $2.00 per lb live weight for kids weighing 30 to 55 lbs respectively. This did not include their transportation costs from farm to slaughterhouse. The previous year prices received from the same buyer were $3.90/lb dressed carcass, slaughter fee was $16 and price to transport carcasses through a refrigerated trucking company averaged $5.00 per carcass.

Table 1.

Prices received per pound live weight for Boer X suckling kids at Easter 2004 for an informal market pool in the NE US, assuming 57% dressing percentage (head on, organs hanging , hide off) and 4% cooler shrink.Live weight, lb |

Dressing % |

Hot Carcass weight, lb |

Shrink from hot to cold |

Cold Carcass weight, lb |

Price per lb |

Price received |

Slaughter costs |

Trans-port costs |

Net with trans-port |

Live price, $/lbwith transport |

20 |

0.57 |

11.4 |

0.96 |

10.9 |

$4.25 |

$46.51 |

$17.00 |

$1.00 |

$28.51 |

$1.43 |

25 |

0.57 |

14.25 |

0.96 |

13.7 |

$4.25 |

$58.14 |

$17.00 |

$1.00 |

$40.14 |

$1.61 |

30 |

0.57 |

17.1 |

0.96 |

16.4 |

$4.25 |

$69.77 |

$17.00 |

$1.00 |

$51.77 |

$1.73 |

35 |

0.57 |

19.95 |

0.96 |

19.2 |

$4.25 |

$81.40 |

$17.00 |

$1.00 |

$63.40 |

$1.81 |

40 |

0.57 |

22.8 |

0.96 |

21.9 |

$4.25 |

$93.02 |

$17.00 |

$1.00 |

$75.02 |

$1.88 |

45 |

0.57 |

25.65 |

0.96 |

24.6 |

$4.25 |

$104.65 |

$17.00 |

$1.00 |

$86.65 |

$1.93 |

50 |

0.57 |

28.5 |

0.96 |

27.4 |

$4.25 |

$116.28 |

$17.00 |

$1.00 |

$98.28 |

$1.97 |

55 |

0.57 |

31.35 |

0.96 |

30.1 |

$4.25 |

$127.91 |

$17.00 |

$1.00 |

$109.91 |

$2.00 |

Table 2 shows an Easter marketing venture where a goat producer decided to become a middleman in 2004. Farmers were paid $1.80 /lb live weight outright for kids weighing about 30 to 55 lbs. Live animal transportation costs by the dealer from the farms to the slaughterhouse averaged $.10/lb live weight and carcass transportation costs from the slaughterhouse 30 miles to the retail buyer averaged $.10/lb dressed weight including ice and gas but not tolls. Carcasses were transported in a refrigerated truck owned by a neighboring vegetable farmer or in ice packed coolers in the back of a pickup truck. Dressing percentages ranged from 54 % to 63 % (average 57 %). The average carcass weighed 24.5 lbs and resulted in a return to the dealer of $18.27 for their phone calls, road tolls, labor, and capital investment.

Table 2. Prices received outright by farmers (paid $1.80 /lb live weight). Return to "dealer" for Easter 2004 after accounting for some marketing expenses. Carcass is hide off/head on, organs hanging.

| Live weight, lb | Price |

Live goat |

Dressing % |

Carcass weight, lb |

Price per lb, |

Price received |

Slaughter costs |

Transport costs |

Net minus expenses |

Live price, $/lb |

Total return |

20 |

$36.00 |

$2.00 |

0.57 |

11.4 |

$4.75 |

$54.15 |

$14.00 |

$1.14 |

$37.01 |

$1.95 |

$1.01 |

25 |

$45.00 |

$2.50 |

0.57 |

14.25 |

$4.75 |

$67.69 |

$14.00 |

$1.43 |

$49.76 |

$2.09 |

$4.76 |

30 |

$54.00 |

$3.00 |

0.57 |

17.1 |

$4.75 |

$81.23 |

$14.00 |

$1.71 |

$62.52 |

$2.18 |

$8.51 |

35 |

$63.00 |

$3.50 |

0.57 |

19.95 |

$4.75 |

$94.76 |

$14.00 |

$2.00 |

$75.27 |

$2.25 |

$12.27 |

40 |

$72.00 |

$4.00 |

0.57 |

22.8 |

$4.75 |

$108.30 |

$14.00 |

$2.28 |

$88.02 |

$2.30 |

$16.02 |

45 |

$81.00 |

$4.50 |

0.57 |

25.65 |

$4.75 |

$121.84 |

$14.00 |

$2.57 |

$95.67 |

$2.34 |

$18.27 |

50 |

$90.00 |

$5.00 |

0.57 |

28.5 |

$4.75 |

$135.38 |

$14.00 |

$2.85 |

$100.77 |

$2.37 |

$19.77 |

55 |

$99.00 |

$5.50 |

0.57 |

31.35 |

$4.75 |

$148.91 |

$14.00 |

$3.14 |

$113.53 |

$2.40 |

$23.53 |

Table 3 illustrates a year round market for very plump suckling or weaned Boer kids weighing approximately 35 to 65 lbs through a farmers' cooperative (now defunct) in Vermont. The cooperative received roughly $5.25/lb dressed carcass from its retailer buyers in 2004. This money was to be paid back to farmers minus the slaughtering costs and a marketing fee of 26% or 22% of carcass price for non-members and members respectively. Farmers had to arrange their own transportation to the slaughterhouse and there was a severe penalty for carcasses that dressed over 35 lbs. It is assumed in Table 3 that 70 and 80 lb goats were weaned and had a lower dressing percentage (52%).

Table 3. Prices received by farmers through a NE marketing cooperative in 2004 after accounting for marketing expenses. Carcass is hide off/head on, organs hanging.

Live weight, |

Dressing % |

Carcass |

Price/lb |

Price |

Marketing |

Slaughter |

Cost |

Total |

Live |

30 |

0.57 |

17.1 |

$5.25 |

$89.78 |

$23.34 |

$15.00 |

$5.00 |

$46.43 |

$1.55 |

40 |

0.57 |

22.8 |

$5.25 |

$119.70 |

$31.12 |

$15.00 |

$5.00 |

$68.58 |

$1.71 |

50 |

0.57 |

28.5 |

$5.25 |

$149.63 |

$38.90 |

$15.00 |

$5.00 |

$90.72 |

$1.81 |

60 |

0.57 |

34.2 |

$5.25 |

$179.55 |

$46.68 |

$15.00 |

$5.00 |

$112.87 |

$1.88 |

70 |

0.52 |

36.4 |

$3.70 |

$134.68 |

$35.02 |

$15.00 |

$5.00 |

$79.66 |

$1.14 |

80 |

0.52 |

41.6 |

$3.70 |

$153.92 |

$40.02 |

$15.00 |

$5.00 |

$93.90 |

$1.17 |

Value-added products are another method farmers can use to receive a higher price for their product. However, heat-and-serve meals and the introduction of goat meat and processed cuts into large-scale retail grocery stores require substantial capital investment. Marketing trim as sausage is a simpler process but the common incorporation of pork fat excludes the Muslim or Halal market. Given our reliable customer base, it is generally important to arrange Halal certification through the Islamic Food Nutrition Council of America (IFANCA) if introducing a product over a wide region.

The amount of capital needed to introduce new or branded products can often be obtained by a very large producer or a "new generation" marketing cooperative. Initial funding to help such cooperatives with their product development may be available through USDA value-added grants, Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education (SARE) grants, and state grants promoting local agriculture. Feasibility studies in areas where the demand for goat meat has already been established are probably not cost effective. However, simple surveys of price sensitivity and testing out what proposed products are of most interest to focus groups and distributors is well advised. Rarely does a co-op have the money to discard one processed product and develop another if investing initially in the wrong choice of product. Focus groups can be picked from goat cheese connoisseurs, patrons of upscale ethnic restaurants featuring lamb and goat, and representatives of goat-consuming cultures with an interest in ready-made meals. Coordination is easier if a cooperative initially forms from a small nucleus of producers that communicate well together. Extra animals can be purchased from nonmembers as long as there is a quality assurance program. The cooperative can be expanded later from this pool of reliable non-members.

Conclusion

The health of the goat meat industry hinges on our ability to sustain and expand a strong "cultural" market from our diverse base of US citizens rather than putting the majority of our marketing resources into trying to build an overseas export market. The interest of an increasing portion of the general public in "ethnic" foods, goat products, lean meats and farm-fresh product can build upon this strong, already-present demand.

Regional marketing service directories such as our Marketing Directory may be very helpful to farmers if funding is available to update and expand them in a timely manner. Land grant institutions, cooperative extension staff, and producer associations can help educate new farmers about market preferences for different ethnic holidays and advantages and disadvantages of different marketing channels. The local food movement can help farmers turned entrepreneurs to market their goat products either direct or through wholesalers eager to purchase US grown goat meat. Thriving local slaughterhouses and packers can help revitalize local livestock dealers and sale barns. Associations such as the American Goat Federation may be able to effectively interact with the American Sheep Industry Association (ASI) on marketing and governmental regulations that impact both lamb and meat goat producers.